My work has been described as emotional, soulful, spiritual, and painterly. These all accurately describe my art. The images are intended to convey a sense of tranquility or create a story that engages the observer, or, simply, is beautiful. – Darlene Yeager-Torre

SS: Most photographers use light to make their images. Tell us what it means to you to paint with light?

DY: Painting with light is done either outside at night or in darkness inside. The exposure time varies from a few minutes to hours and records everything that transpires during that time. The photographer operates in front of the camera as well as from behind it. Daytime photography is recorded in fractions of seconds and freezes time. The photographer works strictly from behind the camera and uses available light which may be supplemented with fill or strobe lighting.

Think of what I do as a painter beginning with a black canvas. Various types of lights are my paint brushes in assorted sizes and colors. Outside, moonlight and stars casts shadows while the light painter moves through the scene selecting individual objects in the environment to highlight by “painting with light” in order to create a center of interest and move the eye through the composition. In the studio, each object will appear on the black canvas only when it is lit. Again, the artist works in front of the camera and moves from object to object. Unlike the daytime photographer, I pre-visualize the finished painting, then practice lighting each scene and continue working until I have the image I want. And, yes, there are happy accidents and surprises most of the time.

SS: Can you tell us about your process and set up for making your work?

DY: Whether working outside in the field or in my studio, my approach is planned and deliberate. I visualize the final image and decide how to best light it before I even begin recording with the camera. I rehearse, either mentally or actually, in advance. Although the lighting is all done in one take in the camera, that final take may come after many attempts in order to get the best lighting for the composition. The still life set ups are based on sound principles of art and also take a good deal of time selecting the items and arranging them into a pleasing composition.

SS: Can you give us some examples of how you created the imagery in your photography?

DY: When I began doing night photography, I quickly learned that the moon moves its own length every two minutes causing it to appear as an oblong blur during long exposures. So, I photograph the moon first then make a separate exposure for the landscape. The moon can be added back to the scene by using an application such as Lightroom or Photoshop. This is the one exception to getting a photo all in one take. Otherwise, I use an exposure of 30 seconds or less for star points instead of star trails, and do the light painting close to the camera in order to finish in time. In the photo, Harvest Moon , the highlighted areas of the corn were made with a tungsten flashlight because tungsten gives a warm glow. I selected the areas to highlight in advance knowing I wanted to move the eye through the lower part of the composition to the moon and back down to the corn.

DY: The North Star is not the brightest star in the sky but it is the one which appears stationary in night photography. As the earth rotates on it’s axis, star trails are created with the longest trails being farthest from the North Star. In North Star over Cornfield , the left side of the photo was lit with an off-camera strobe. It was a very cold night and I didn’t want to run the length of the cornfield popping off my flash so I used the headlights from my car. This is the largest light I’ve used so far. The brightness on the horizon is light pollution a city miles away.

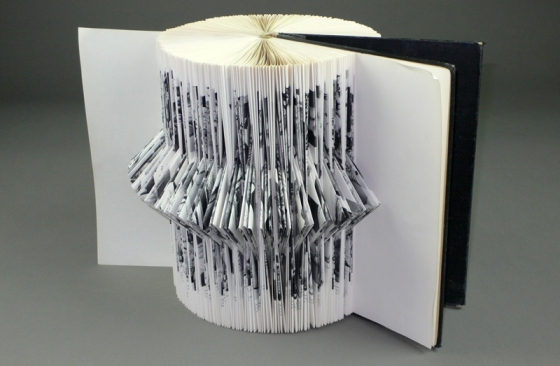

DY: In my studio, a still life begins with an interesting composition which may take as long as 2 hours to build such as Party, Party. After practicing the best way to light each individual object, I turn out all lights and begin the exposure. I wear black including long black gloves so the camera thinks I’m part of the darkness and does not record my image. In this photo my instruments included a book light, keychain light, and small LED flashlight. The smaller lights were tilted in such a way on some of the objects to make them appear as if they are glowing.

DY: Missing You was made following the death of my cousin. The portraits on the table are his parents who would have remembered reading by the light of an oil lamp in their youth. The empty chair in the shadows represents my cousin. Therefore, I consider this a portrait, not a tabletop still life or interior. I have since made more narrative portraits, each with a distinctive personality. As in the landscapes, what is left in the shadows is equally as important as those things painted with light.

SS: How were you introduced to creating photography specifically in this way?

DY: In October of 2010, I attended an educational presentation about night photography by Dick Wood for the Westbridge Camera Club. I started taking long night exposures that month. Paula Hardin, who curated this exhibit and is also a member of Westbridge, has long been a night photographer and is an experienced light painter. We began going out on shoots together and she introduced me to the concept and some of the techniques of painting with light. It added a whole new dimension to my work and appealed to me because it is so complex.

SS: What are the most important influences that have moved you as an artist?

DY: I can’t say any particular artist influenced me because as an art teacher I have seen thousands upon thousands of fine art images in all media, across cultures, styles, and genres. As I researched work in order to teach the art history and art appreciation segments of the curriculum, I learned, along with the students, how to look more carefully and deeply at art. I suppose I would have to say it is the cumulative effect of a wide range of works that have impacted me. That may change, of course, in the future.

SS: Are there any places you visit to inspire your art making?

DY: I spent my childhood on the family farm where I developed a profound respect for the beauty, variety, and complexity of the natural environment. I suspect it will always be nature that replenishes me. Having said that, it is equally important to remain creative wherever I am. My job as an artist is to make the ordinary seem extraordinary. Who could possibly visit a place like Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, or the vast ocean and not be inspired? For me, those experiences are limited so it is crucial that I find beauty and inspiration in some of the tiniest things in nature. And, let’s not forget to look up every night. Even in the suburbs, the stars, moon, and/or clouds appear in the sky every night.

SS: You recently received a grant to further your study in light painting. Can you tell where you received the grant for funding?

DY: Yes, I received a Professional Development, Artist in the Community grant from The Greater Columbus Arts Council. It helped fund a four-day seminar on night photography and painting with light in California.

SS: How did you find out about this opportunity?

DY: I learned about the grant when Ruby Classen from GCAC gave a presentation at the Ohio Art League in March. Her presentation was so thorough and she was so enthusiastic and encouraging that I went home and began the application immediately.

SS: Can you tell us about the trip to California?

DY: The workshops were presented by some of the most accomplished and respected contemporary night photographers including Steve Harper, Lance Keimig, Tim Baskerville, Troy and Tom Paiva, and Susanne Friedrich to name just a few.

The morning and afternoon sessions were about both the technical aspects and creative methods of long exposure, night photography. The topics included field preparation, camera settings, high ISO testing, image stacking, and light painting methods. After a dinner break the evenings were devoted to shooting at various sites with the workshop leaders and other participants. We usually worked on location until about 1 a.m. and sometimes later.

SS: What did you take from the experience?

DY: The most valuable part for me were the technical workshops and also learning how these artists, who have been working at night and in low-light, long-exposure photography for up to 30 years, approach it. I was interested to learn that they too make many exposures of a single scene until they achieve just the effect and lighting that they envision. Not one advocated clicking off a whole series of shots and later creating a composite image using an application such as Photoshop. It was reassuring to learn that I’m not the only photographer who goes to a location, walks around surveying it, sets up for an exposure, runs a few test shots, then begins working the scene and continues for several hours – or more – until satisfied with the results.

SS: Did you learn anything unexpected?

DY: The most unexpected experience came after everything else was said and done. Somewhere between Reno, Chicago, and Columbus I lost the camera memory card containing all the images I took that week. It contained some once-in-a-lifetime images including a lunar rainbow over Yosemite falls, two nights worth of images taken at Bodie Ghost Town (access at night by workshop participants only and with special, advance permission from the parks services), and more.

Ordinarily I would have experienced an overwhelming sense of loss, frustration, and despair. Instead, I realized that the knowledge I gained during the week cannot be lost nor compromised. It will be with me and remain intact as long as I practice night photography. A final benefit . . . if I ever do have a lapse in memory . . . I now know other night photographers, including the instructors, whom I can call upon for help and advice. I can’t think of anything more valuable than that knowledge and camaraderie.

This article was written and published for The Artists’ Interview,(www.theartistsinterview.com) by Stephanie Sypsa.